Introduction to Australian Tax Residency

Below is a summary of Australia's current approach to determining an individual's tax residency - but it important to appreciate that the Australian Government indicated in 2021 that it would, "replace the individual tax residency rules with a new, modernised framework".

The intention of the new framework is to include a simple ‘bright line’ test — a person who is physically present in Australia for 183 days or more in any income year will be an Australian tax resident. Individuals who do not meet the primary test will be subject to secondary tests that depend on a combination of physical presence and measurable, objective criteria.

![]() Australian expats should be aware of proposed changes to how tax residency will be determined in the near future. These changes could profoundly impact the tax residency status of Australians who return home for relatively short periods of time (45 days or more in a tax year).

Australian expats should be aware of proposed changes to how tax residency will be determined in the near future. These changes could profoundly impact the tax residency status of Australians who return home for relatively short periods of time (45 days or more in a tax year).

The Australian Treasury released a Consultation paper on the proposed New Tax Residency rules which required feedback required by September, 2023. Despite the substantial interim period we have yet to hear the Government's formal response to feedback and there has been no no mention of any changes in subsequent Federal Budget.

Consequently, the earliest any changes to the rules can now be implemented is July 1, 2025 and that looks very unlikely given an intervening Federal election. July, 2026 now looks to be the earliest prospective date but we are beginning to wonder whether the proposal has in effect been "shelved", given very much larger priorities at present.

We have allocated a separate page to considering the detailed impact of the New Tax Residency Rules and developed a New Tax Residency Rules Flowchart to illustrate how it would apply in practice.

Current Australian Tax Residency Rules

Departing Australia

In general, although it is stressed that any assessment of tax residency is very dependent on individual circumstances, most Australians who leave the country with their immediate family with the intention of residing outside the country for two or more years and establishing a home overseas are likely to be treated as non-resident from the date of departure. Note that, very recently, we have seen the ATO begin to accept that an individual may become non-resident even if their spouse or partner remains in Australia, but this needs particular advice.

Non tax residency means that expatriates will not be liable for Australian tax on their offshore income, but remain liable for Australian tax on their Australian sourced income (e.g. rental income). Clarity with respect to your tax residency is a matter of utmost importance - particularly if you are moving to a low or no income tax regime - and you should seek professional advice before moving overseas and indeed signing any employment contract.

Resuming Tax Residency in Australia

Once your overseas assignment is over and you decide to return home, not only are you are coming home to family and friends but you are also coming home to a complex taxation system. There are some important issues to bear in mind, and ideally address, before you return to Australia.

When you return to Australia with the intention of staying permanently you will generally be treated as a resident for tax purposes from the date of your return. This means that you will become subject to tax on your worldwide income and liable to capital gains tax on the sale of assets, no matter where they are located. In addition, there are some special rules associated with the application of Capital Gains Tax (CGT) and the taxation of pension benefits.

Current Tests of Tax Residency

As we mention above, tax residency can be a complicated area and any determination is very dependent on an individual's personal circumstances. However, we cannot stress enough the importance of clarity around the issue of residency and a failure to address this issue can prove to be an exceptionally expensive oversight. We very generally cover the tests of residency below but, as mentioned above, a review of tax residency is currently underway.

In short, an individual is primarily a resident of Australia for taxation purposes if he or she resides in Australia within the ordinary meaning of the word "resides". However, residence in the normal sense is quite different from the notions of domicile and nationality. For example, a taxpayer may be held to be resident in Australia, "even though he lived permanently abroad, provided he visited Australia as part of the regular order of his life."

A person need not "intend to remain permanently in a place" to be found to reside there, but it seems that where the relative length or shortness of their stay in Australia is not decisive, the circumstances in which the person went and stayed have to be considered. The Tax Office treats every case on its own particular merits.

Some common situations, and the Australian Tax Office's (ATO), approach in terms of residency are covered in the table below:

| If you... | Then you... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

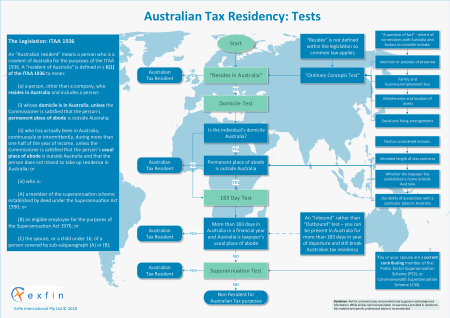

There are four tests of residency contained within the definition of 'resident' in subsection 6(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA). They are alternative tests in the sense that even if an individual is not a “resident” according to ordinary concepts (see a) below) within the common definition then they may fall within one of the other tests. The four tests for residency are:

- Residency – the “resides” test

- Residency – the “domicile” test

- The 183 day rule, and

- The Superannuation test

The flowchart below provides a general overview of the tax residency tests and then we explore them individually in more detail below.

A. Residency according to "ordinary concepts"

This test provides that whether a person resides in Australia is a question of fact that depends on all the circumstances of each case, with the following factors to be considered:

- Whether personal effects are kept in Australia or in the country of origin.

- The extent to which any assets or bank accounts are acquired or maintained in Australia and in the country of origin.

- Whether a migrant has commenced or established a business in Australia.

B. The domicile test

An individual is a resident of Australia under the domicile test if he or she has a domicile in Australia unless the Commissioner is satisfied that the person's permanent place of abode is outside Australia. Under the Domicile Act 1982 , a person acquires a domicile of choice in Australia if the person intends to make his or her home indefinitely in Australia. The domicile test is discussed in Taxation Ruling IT 2650. Domicile generally means the country in which you were born unless you migrate to another country - then you adopt a "domicile of choice".

C. The 183 days test

A returning expatriate or new migrant having regard to their terms of their migrant visa, who is present in Australia for more than 183 days (continuously or intermittently) in a tax year is, generally speaking, considered a tax resident of Australia. This is unless the Commissioner is satisfied that their usual place of abode is outside Australia and that they do not intend to take up residence.

D. The Superannuation Test

This is a “statutory” test and an alternative to the ordinary tests of residence – that is to say that individual’s may be “resident” under this test when they do not in any way reside in Australia in the ordinary sense. In effect individuals are “deemed” to be residents if they, “are an eligible employee for the purpose of the Superannuation Act 1976 or is the spouse or a child under 16 years of age of such a person." This test applies mainly to people working for the Australian Government overseas.

Dual Residency

It is possible for an individual to be tax resident in two countries concurrently, in other words to to have dual tax residency. For example, an overseas assignment may not be long enough to see you break Australian tax residency but long enough to have you considered a tax resident in your new country of residency - for example, a one year assignment to the UK or Japan.

In that situation, a Double Tax Agreement (DTA) may operate to determine each countries taxing rights and ensure that you do not, as the name of the agreement suggests, pay tax in both countries on the same income. Australia has entered into DTA's with a wide range of countries and the treaties will prevail over local legislation to the extent that they are inconsistent. These treaties often follow certain models (e.g. the OECD model) but there can be peculiarities and individual advice will often be required for expatriates in areas such as pensions and capital gains.

Employees on Private Yachts and Cruise Ships

We have always been surprised at the number of of Australians employed on international private yachts and cruise ships. They are often employed on contracts with foreign based firms with salary paid into overseas bank accounts with no tax deducted - with employers indicating that they are working in "international waters" and no tax is payable. Expats then often simply cease to submit Australian tax returns and later return to Australia, often after many years, believing that they were working outside the Australian tax system. In fact, that is often not the case, and they continue to remain Australian tax residents unless they had become tax resident elsewhere in the world - with the result that the ATO may attempt to recover Australian tax on their income for the relevant period.

The fact that an individual lodges a "Return Not Necessary" form, on the basis that they regard themselves as non-resident, does not mean the ATO will simply accept that there has been a break in residency - the relatively recent case of Duff and Commissioner of Taxation (2022) is a good example of the challenges involved in establishing non-residency, particularly in terms of the domicile test in this particular situation.

In this case, Duff had argued that a person who lived on a cruise liner became a domicile of the flag state – Norway in this situation. This was rejected by the judge, as was the argument that Duff's "permanent place of abode" was the ship's cabins during his period of employment - on the basis that the phrase "permanent place of abode require the identification of a single country in which the taxpayer is living/residing permanently".

More Background

For those looking for more background in terms of how tax residency is determined, the ATO has recently released a Final Taxation Ruling, "Income tax: residency tests for individuals", which provides some guidance on how tax residency will be assessed. The Ruling replaces longstanding guidance provided in IT 2650 and TR 98/17, effectively combining the content and updating it in terms of recent case law. We have made the Ruling available below but stress that assessments in relation to residency are usually complex in practice and require professional insight.

Income tax: residency tests for individuals: Final Taxation Ruling: TR2023/1

Maintaining a Travel Log

As a matter of practice, given that incoming and outgoing stamps are no longer placed in passports, and bearing in mind the prospect of new tax residency rules, all expats should maintain a log containing dates of entry and exit from Australia and flight numbers. This can be important information in terms of determining residency and the ATO has access to precise data from immigration records.

If you would like to arrange professional advice please complete the Inquiry form below providing details and you will be contacted promptly.